Almost one year ago, the U.S. economy looked like it was teetering on the edge of a recession. Hiring was faltering, unemployment was rising and annual revisions to employment tallies showed that the job market was in worse condition than previously estimated. Realizing the economy wasn’t as strong as they had believed when they last met, the Federal Reserve in September cut interest rates for the first time since the pandemic.

Today, the U.S. central bank finds itself in a similar predicament. A recent string of weak jobs reports may convince policymakers to resume cutting rates when the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) wraps up its two-day meeting on Sept. 17.

But this time, a new challenge looms: Inflation is on the rise again, drifting further away from the Fed’s 2 percent target. Some Fed officials fear that cutting rates too soon as tariffs continue pushing prices higher could repeat the central bank’s mistakes of the 1970s. That delicate combination of rising prices and weakening employment, often referred to as stagflation, could leave the Fed with fewer tools — and less conviction — to cushion the economy’s slowdown.

It is clear the economy is caught between a rock and a hard place — or more accurately, between a labor shock and a hot pace. Concerns over stagflation, marked by rising prices amid weakening economic growth, are likely to intensify as the Federal Reserve weighs its next move. The Fed’s dual mandate of stable prices and full employment remains firmly at odds.

– Stephen Kates, CFP, Bankrate financial analyst

The Fed will cut rates in September, but how big will it be?

A sharp slowdown in hiring this summer has made a September rate cut appear all but certain. Investors see a near 90 percent chance that the Fed cuts this month, according to CME Group’s FedWatch tool.

The once-revered U.S. labor market doesn’t look so strong anymore. Employers added just 22,000 jobs in August, and in June, the economy lost jobs for the first time since 2020, according to the latest report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Without gains in health care, job growth would have turned negative for three of the past four months, BLS data shows. Job cuts, meanwhile, are now spreading beyond the government and professional services industries and into construction and manufacturing.

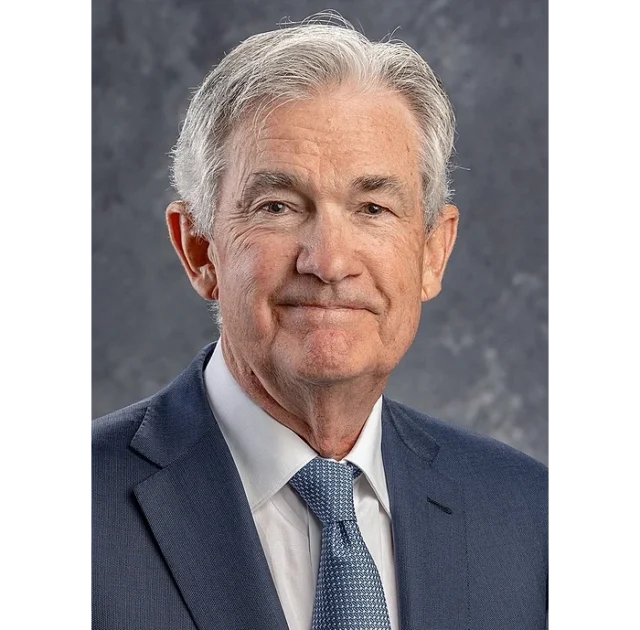

Fed Chair Jerome Powell didn’t dissuade investors, saying in an August keynote that those shifting labor market dynamics “may warrant adjusting our policy stance.”

But he also admitted the Fed’s two goals — stable prices and full employment — are now “in tension” with each other. Analysts say that makes the Fed most likely to cut borrowing costs by a quarter of a percentage point, though some say they could see a case for a bigger cut.

Last year, the Fed decided to cut interest rates by half a percentage point when it faced similar downside risks. Inflation, however, was at a pandemic-era low of 2.4 percent.

“There is growing evidence that labor market softness is weighing on consumers’ willingness to spend and that businesses are hesitant to invest,” says Gregory Daco, chief economist at EY. “I don’t really see much reason to delay larger moves in monetary policy when the Fed is behind the curve.”

Fed Governor Christopher Waller, who dissented against the Fed’s decision to leave interest rates alone at its last meeting in July, believes that the slowdown in the labor market could not only suffocate inflation — but derail the entire economy. Powell himself appeared like he was coming around to that view in his pivotal Jackson Hole address last month.

It is possible “that the upward pressure on prices from tariffs could spur a more lasting inflation dynamic,” he said. “Given that the labor market is not particularly tight and faces increasing downside risks, that outcome does not seem likely.”

But other more inflation-minded members of the committee aren’t ready to conclude that a slowdown in the labor market will be enough to extinguish tariff-driven inflation.

Patrick Harker, former president of the Philadelphia Fed, would be one of those officials if he were still on the committee, the official said in an interview with Bankrate. He still hears from business contacts that they’re holding off on raising prices — for now — but they can’t stay put forever.

Going forward, let’s see what happens with inflation. We have a very murky lens that we’re looking through because of the impact of tariffs. Being cautious here is appropriate.

– Patrick Harker, former president of the Philadelphia Fed

How far, and how fast, will the Fed move to keep cutting after the September meeting?

When Harker retired in June, the policymaker said he had two rate cuts penciled in for 2025. That’s even while penciling in one of the highest forecasts for the unemployment rate among the FOMC: 4.5 percent.

“I still think that’s appropriate,” he said. “Despite all the turmoil, [the economy] pretty much rolled out the way I thought it would.”

Investors expect officials to also debate at their September meeting whether to continue cutting interest rates at their next two meetings in October and December. Last year’s September cut was the first in a series of three, with policymakers reducing borrowing costs a total of one percentage point.

Disclaimer

Artificial Intelligence Disclosure & Legal Disclaimer

AI Content Policy.

To provide our readers with timely and comprehensive coverage, South Florida Reporter uses artificial intelligence (AI) to assist in producing certain articles and visual content.

Articles: AI may be used to assist in research, structural drafting, or data analysis. All AI-assisted text is reviewed and edited by our team to ensure accuracy and adherence to our editorial standards.

Images: Any imagery generated or significantly altered by AI is clearly marked with a disclaimer or watermark to distinguish it from traditional photography or editorial illustrations.

General Disclaimer

The information contained in South Florida Reporter is for general information purposes only.

South Florida Reporter assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions in the contents of the Service. In no event shall South Florida Reporter be liable for any special, direct, indirect, consequential, or incidental damages or any damages whatsoever, whether in an action of contract, negligence or other tort, arising out of or in connection with the use of the Service or the contents of the Service.

The Company reserves the right to make additions, deletions, or modifications to the contents of the Service at any time without prior notice. The Company does not warrant that the Service is free of viruses or other harmful components.