If the White House gets its way, ordinary Americans will be able to invest their retirement savings in the private equity market.

President Donald Trump is expected to direct the Department of Labor and the Securities and Exchange Commission to give employers and 401(k) plan administrators guidance on how to incorporate private investments within retirement accounts, the Wall Street Journal reported Wednesday.

This is the first step toward a potential big win for private equity, and it didn’t come cheap. The slice of the financial services industry that includes hedge funds donated more than $200 million to Trump’s 2024 campaign, contributions records show.

Proponents of adding private equity investments to retirement plans — mostly private equity firms themselves and organizations that represent their interests — say giving Americans access to these instruments can help them diversify their portfolios. The number of public companies in the U.S. has dropped by about 3,000 over roughly the past 30 years, according to the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth University. Private equity companies are positioning themselves as an alternative.

Earlier, the Journal said big investment companies, including Vanguard, BlackRock and Empower were planning to roll out private equity instruments for 401(k) investors. It also noted, though, that the president’s executive order is just a first step, and not everyone is as enthusiastic about the possibility.

Why not everyone is convinced

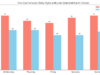

Plan sponsors are likely to remain leery of private equity as long as they face a risk of being sued by accountholders over the high management fees private equity firms charge. Management fees on private equity investments are much higher than those that 401(k) investors typically pay. According to the Investment Company Institute, the average expense ratio for mutual funds invested in stocks dropped by 62% between 1996 and last year. In 2024, the average fee was 0.4% — or about one-fifth of a typical private equity management fee. Fees for passively managed funds that track the performance of an index like the S&P 500 can be even lower.

What’s more, not everyone is gung-ho about the idea of letting private equity firms get their hands on some of the roughly $12 trillion American workers have socked away into 401(k)s. Some people worry that ordinary Americans won’t really know what they’re getting into. The concern is that retirement savers could make investment choices that don’t justify what they’re paying — or worse.

In a letter to Empower, one of the private equity firms advocating for giving 401(k) investors access, Sen. Elizabeth Warren criticized “risky, expensive private markets” and questioned whether ordinary people with limited investing skills or education would really benefit from having this option in their 401(k)s.

“Private funds have weak transparency, liquidity, and compliance requirements and lack investor protections,” Warren wrote in a follow-up missive to Empower. She stressed the need to protect investors — and the nest eggs they spent decades building — from taking risks they don’t fully understand with money they can’t afford to lose.

One of the factors that can make these instruments so complex is their high leverage. While this offers the potential for higher returns, it also raises the risk of greater losses. In addition to their complexity, private investing doesn’t take place in a large, transparent, liquid market. Putting money into private equity could mean potentially tying it up for years in exchange for the promise — but not the guarantee — of higher yields than plain-vanilla investing could deliver.

A new study from a faculty member at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School warned about the heightened risks investors face. Jeffrey Hooke, a senior finance lecturer and author of the study, said the lack of regulation and transparency are concerning downsides. He also found that these investment vehicles often failed to beat the stock market’s overall performance or deliver returns much higher than an investor could get with an ordinary portfolio of stocks and bonds.

Hooke also took issue with the cost, telling an investment industry trade publication that there is “a long period of time for the private equity fund to be collecting fees” before the investor sees any gains. A Carey Business School article about the research summed up the primary concern with adding private equity to retirement accounts. “These riskier investment vehicles may not align with the financial security and predictability most 401(k) participants expect,” it said.

Disclaimer

The information contained in South Florida Reporter is for general information purposes only.

The South Florida Reporter assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions in the contents of the Service.

In no event shall the South Florida Reporter be liable for any special, direct, indirect, consequential, or incidental damages or any damages whatsoever, whether in an action of contract, negligence or other tort, arising out of or in connection with the use of the Service or the contents of the Service.

The Company reserves the right to make additions, deletions, or modifications to the contents of the Service at any time without prior notice.

The Company does not warrant that the Service is free of viruses or other harmful components